The Care Apartment as Typology

written by Lorna Gibson-Tjebbes, 12.01.2026

The building described below originally integrated several spatial features that supported aging in place: generous apartment sizes, guest rooms, small studios for family or carers, and a centrally located concierge apartment connected to a shared garden. Together, these elements formed a coherent care-oriented housing model, without being labelled as such.

We propose to understand the former concierge dwelling as a “care apartment”: a unit owned by the VvE and rented to professional carers willing to live on-site, potentially with their families. In exchange, carers provide varying degrees of support to residents while becoming part of the social fabric of the building. Care is not organised as an external service, nor isolated in an institution, but embedded in everyday life. This model offers several strategic advantages; It supports aging in place without medicalising the residential environment, It provides housing for care workers in a city where key workers struggle to find affordable homes, it strengthens informal social networks and continuity of care at the scale of the block, it treats care as shared infrastructure, rather than an individual responsibility.

At a time when housing policy increasingly relies on informal care networks and longer independent living, spatial models that enable proximity, dignity, and mutual support are essential. The Beethovenstraat building demonstrates that such models already exist within Amsterdam’s housing stock, and that strategic renovation decisions can either erode or reinforce them. Rather than viewing care as a cost or exception, this case suggests it can be designed, governed, and spatially embedded as part of everyday housing environments. The challenge for future housing and urban programmes is not only to build more homes, but to recognise, adapt, and replicate such typologies at scale, across new developments, renovations, and collective ownership models.

reimagining the concierge apartment

Beethovenstraat 186–196, Amsterdam

Architect: J.W. du Pon (1922–2008)

Landscape Architect: Mien Ruys (1904–1999)

Built: 1961

Programme: 16 apartments for seniors

Location & Context

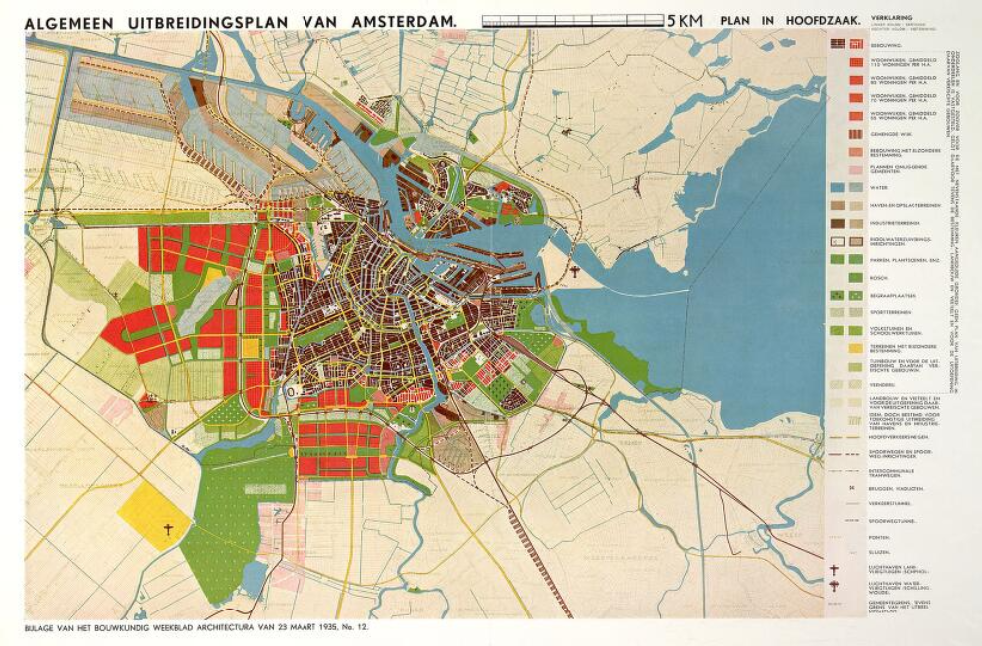

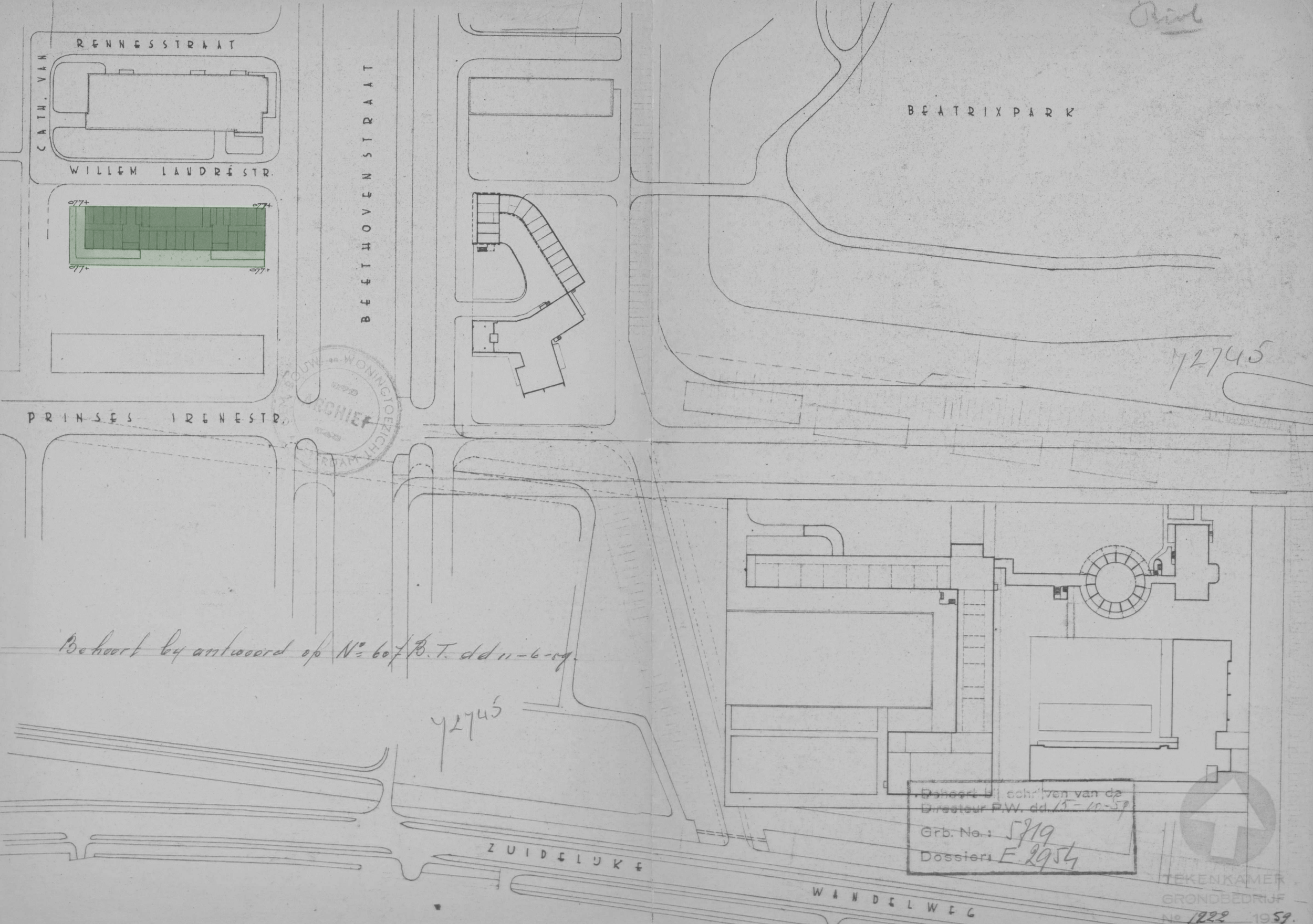

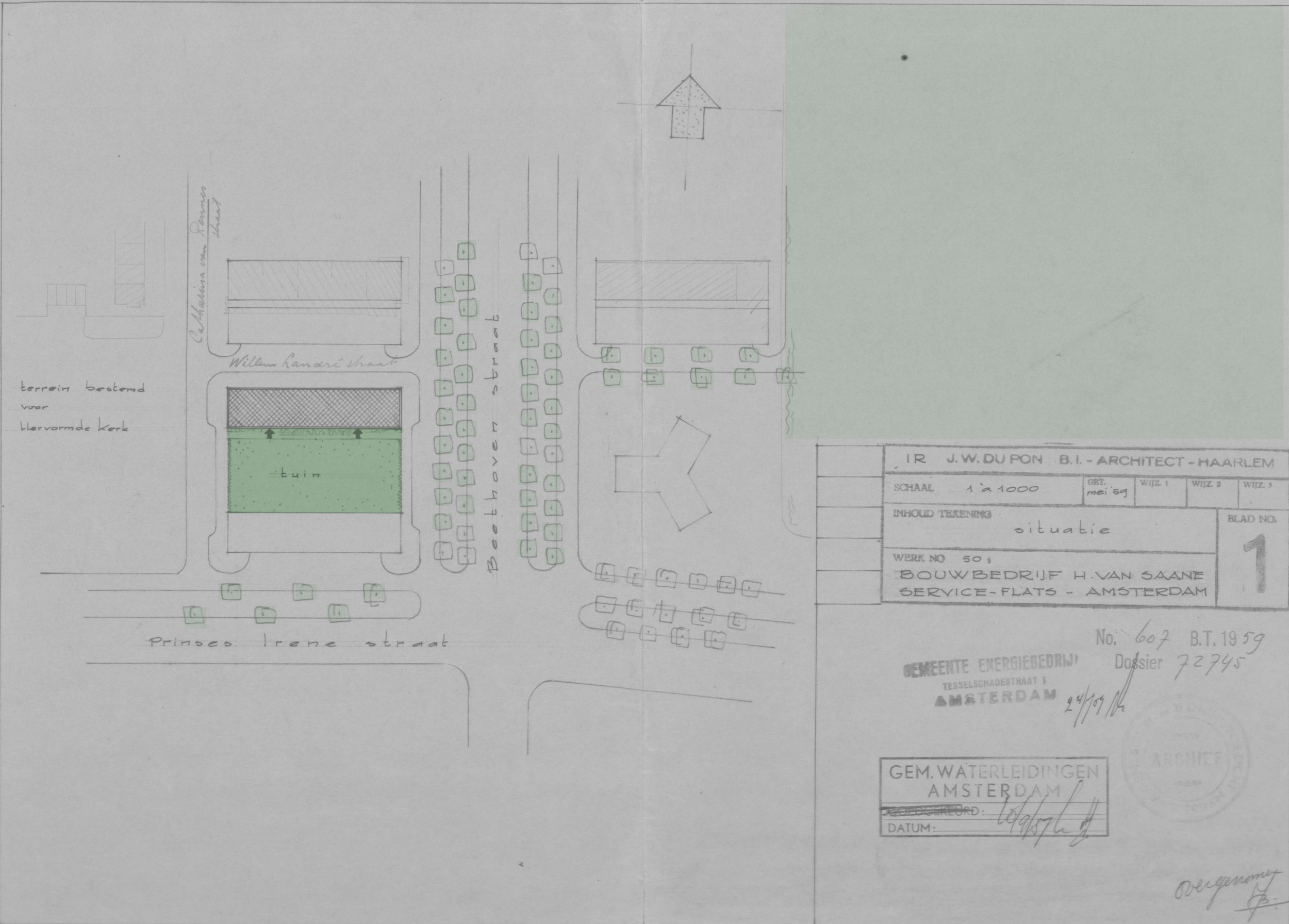

The longitudinal slab apartment block has its main entrances on Beethovenstraat via a private garden, with a rear entrance on Willem Landréstraat. Its location was designated for a housing area with a density of 85 apartments per hectare in the 1935 AUP plan (van Eesteren, no.12). Including the studios and concierge apartment, the actual density is slightly higher, at 102 apartments/hectare, with an FSI of approximately 1.3. It is one of a series of slabs along the street that are divided by a road of a garden.

Perpendicular to the busy Beethovenstraat, the apartments face a large shared garden designed by landscape archtiect Mien Ruys, renowned for her modular planting designs in public housing and her iconic Tuinen van Mien Ruys in Dedemsvaart. The garden is beautifully maintained by residents and provides a quiet oasis for leisure, garden parties, and informal social interaction, a rare sense of separation from the bustle of the city.

Entrance, Routes, and Connections

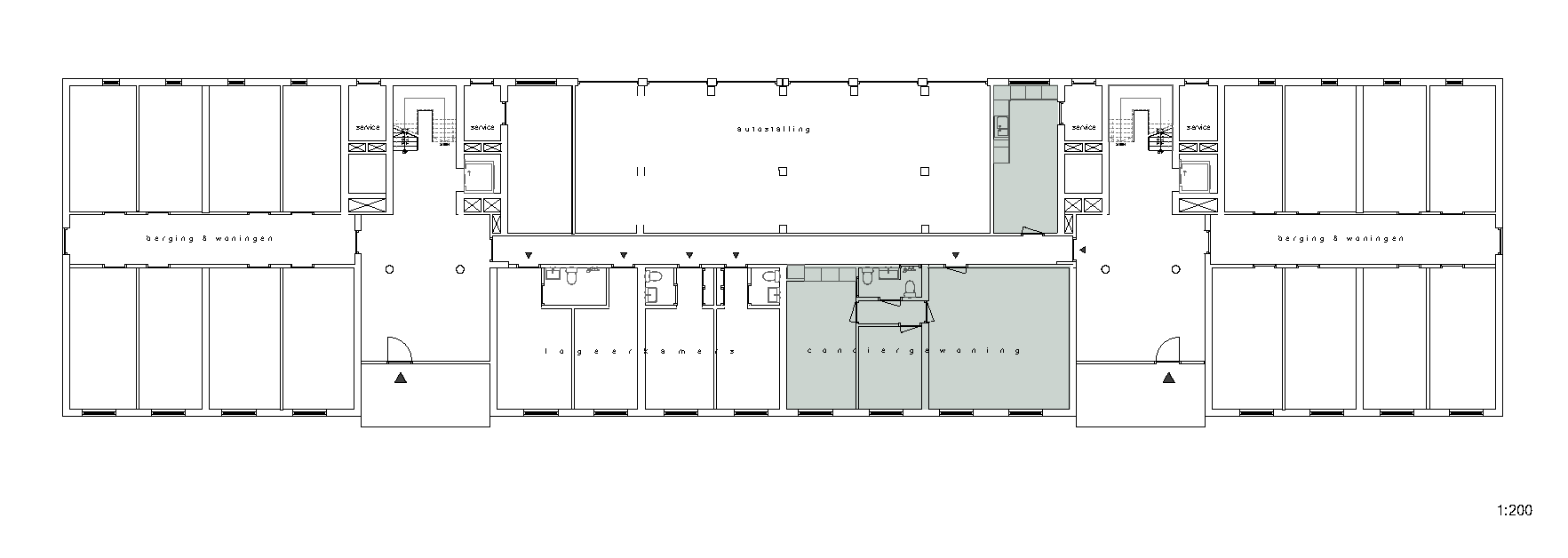

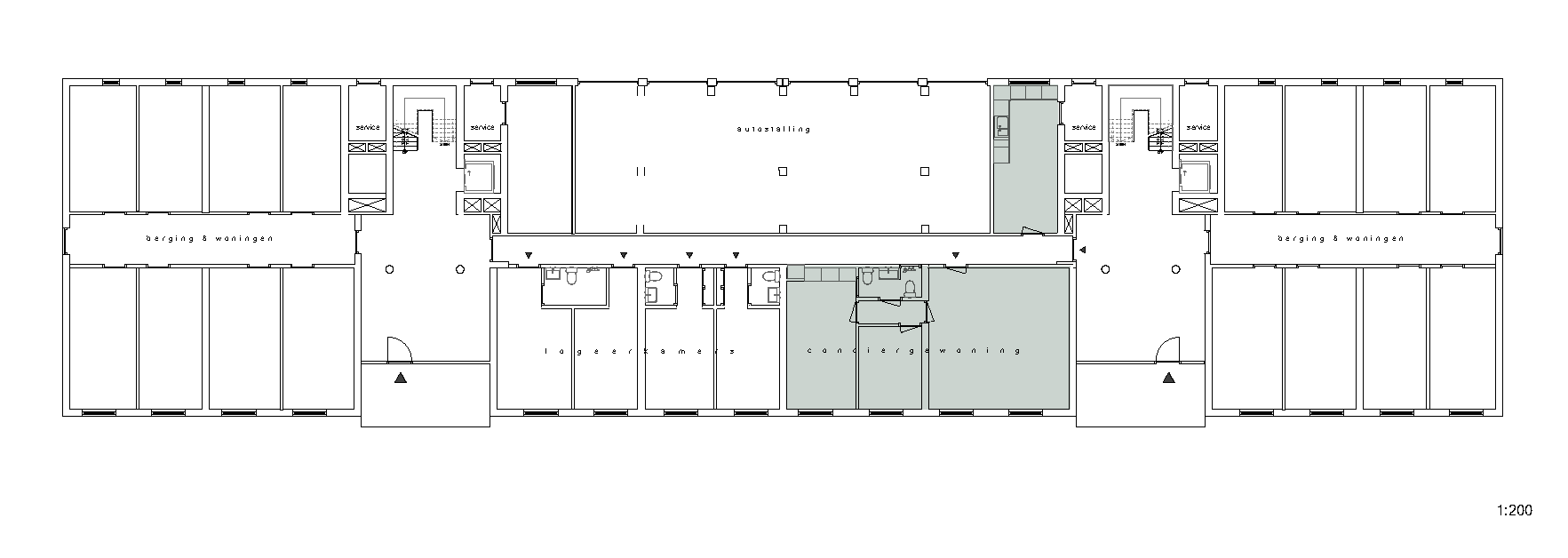

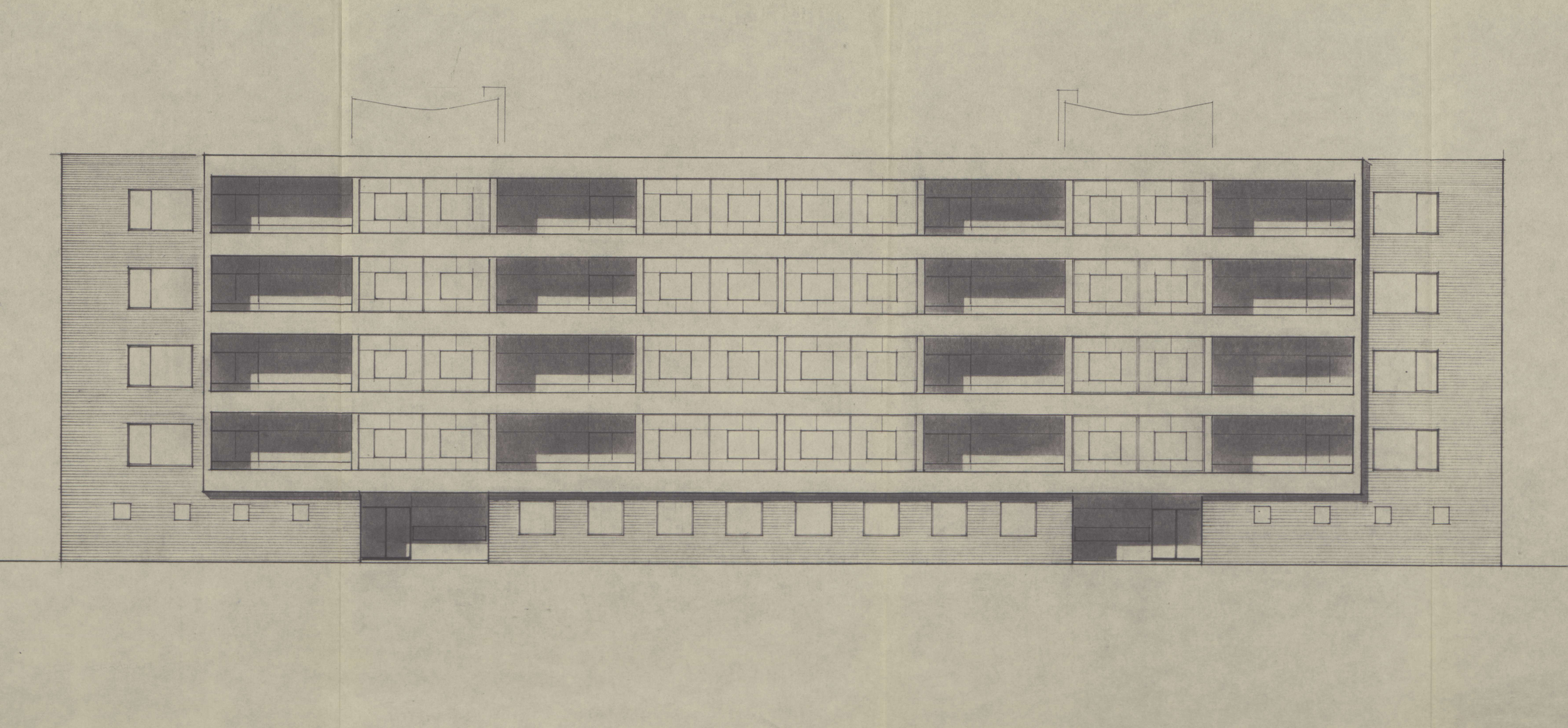

The two main entrances on the south side are clad in hardwood and tiled with travertine stone, standing out against the yellow brick and grey plate modernistic façade. A glass wall separates the garden from the entrance halls, housing post boxes and potted plants. Corridors connect the entrance halls to storage, four ensuite guest rooms, a concierge apartment with two bedrooms and a communal kitchen, and a rear utility entrance. Five parking spaces are integrated into the north side of the ground floor.

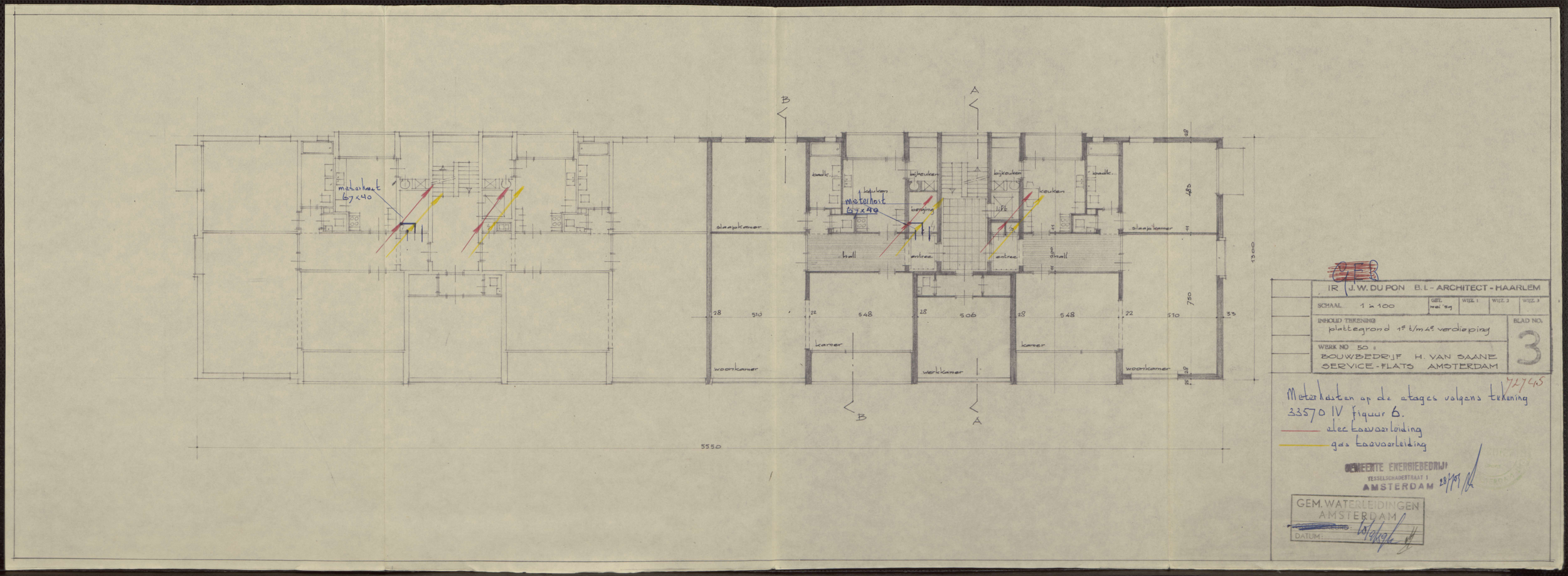

Wide staircases with split landings connect each floor, supplemented by lifts tucked nearby. Each landing serves three apartments: two spacious 1-bedroom apartments (~130 m²) and one 30 m² studio. Many studios have been combined with larger apartments or are used to host visiting family. Large apartments have two balconies, one extending the living area toward the south garden (~7.5 m²), the other extending the kitchen to the north (~3.5 m²), with full glass facades framing views of the garden in ways that turn it into a series of living artworks.

Apartment Interior Programming

We have visited many of the renovated and original apartments, and renovated two ourselves. Both renovations involved moving the kitchen from the north façade into the living space, converting the former kitchen into a guest bedroom with ensuite and utility room. In one apartment, a new opening was created to connect the master bedroom with the main bathroom for improved accessibility.

Beyond environmental and interior improvements, both clients prioritized flexible privacy: spaces that allow residents to be comfortably alone but also to host guests. While this level of spatial freedom is a luxury, it is worth noting how important it is for these senior inhabitants symbolic and psychological well-being.

The “Care Apartment”

Coming back to the ground floor, the concierge apartment is where we have been ask to renovate and transform this special typology into something that structurally divides the two sides of the block and is sellable. But approaching the renovation whilst maintaining it’s strategic positioning it could take the form of something more special, we’ll call the “care apartment”. This idea suggests, the apartment is owned and rented by the VVE, to carers prepared to live on-site with their families. They support and look after the residents at varying degrees, while becoming an integral part of the community. At 120 m², the apartment overlooks the 500 m² communal garden, creating a generous and comforting environment for both carers and residents.

This is a rare and socially innovative example: care is not a struggle, something to ignore or hidden away in institutions, nor is it entirely privatized. Instead, it is embedded in everyday life, recognised as part of the city’s infrastructure and integrated into its social fabric of the block. Carers have a stable home, their work is respected and visible, and the residents benefit from continuity and connection. The studio apartments, would no longer be required for care and could be sold to further diversify the mix of the block with starters or singles.

In a city where health and education workers struggle to find housing, and where the demands of care continue to grow, this typology offers a model worth preserving and learning from. It illustrates how architecture and urban planning can actively support care as a societal function, not just a private service. As Tim Robertson argues in his 2025 book The Care Economy, integrating care into the built environment - and making it visible, spatially and socially - is a vital part of creating sustainable, humane cities.

The Beethovenstraat apartment shows that architecture can do more than house individual needs: it can shape social relations, support well-being, and embed care into the rhythms of everyday life. The challenge for the future is to recognise and replicate this typology, adapting it to new buildings, larger developments, and evolving urban contexts, so that care becomes a shared, socially integrated, and spatially supported asset rather than an afterthought.